The opposable thumb, the large brain, the fire: These things have helped us conquer and surpass numerous inferior creatures. I mean, we get silk from worms, burn ants at our leisure, tell elephants what to do. And yet the feathered beings of our world lord it over us (most of them, anyway). Always swooping and gliding and diving and climbing. Ever looked a seagull in they eye? Nothing but scorn.

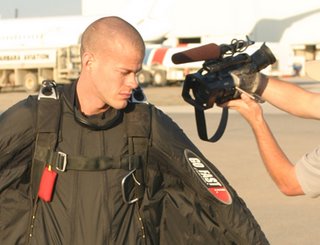

The opposable thumb, the large brain, the fire: These things have helped us conquer and surpass numerous inferior creatures. I mean, we get silk from worms, burn ants at our leisure, tell elephants what to do. And yet the feathered beings of our world lord it over us (most of them, anyway). Always swooping and gliding and diving and climbing. Ever looked a seagull in they eye? Nothing but scorn.Now, I've tried to make the point that in the last few years we've made some progress in reducing this appalling gap between what we can do and what a bird can do. Going up, of course, is still the major hurdle, but birds do a few other things we'd like to manage. Namely, fly together. Flocks, they call them, and the word has been co-opted by the bird imitators of our time. Until now, though, human flocks have been fairly small. But this July, over Cochstedt, Germany, 70 wingsuiters will pour out of an Antonov 72, fly about together, and, with luck, enter the Guinness Book of World Records (for the greatest number of wingsuiters exiting a plane at one time). Each skyflyer will be provided with a smoke canister, so the view from the ground, to say nothing of from the heavens, ought to be streaked with glory.

Getting out of the plane will be the easy part of the event. "Organizing this is like trying to herd cats," says Scott Campos, a BirdMan Chief Instructor and author of Skyfling: Wingsuits in Motion, who's helping to put the flock together. "The logistics of setting up an event extend all the way down to things like porta potties, city and vendor licenseing fees."

As for flying cats—stay tuned.